7514 N. Central Ave./ 10 W. Orangewood

This imposing, but very well hidden, Victorian home is one of less than 50 pre-1900 homes that still exist in Phoenix. It was built by William J. Murphy, a businessman and developer who moved to Arizona from Ohio in 1880 and initially worked for the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad before prospering as a developer. Murphy is credited with building the Arizona Canal in 1885, developing the city of Glendale, and introducing citrus and sugar beets to the area. Murphy is also responsible for building Grand Avenue in order to draw people from the growing city of Phoenix to the new towns of Peoria and Glendale.

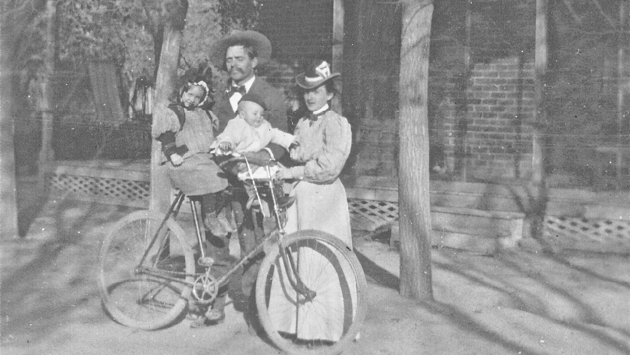

In 1895, Murphy purchased 10 acres along along Central Avenue where he built a ranch for his family, including this large Victorian home. He saw the agricultural potential of land along the canal and planted over 1,800 citrus trees, imported from California, on his ranch — marking the birth of the citrus industry in Phoenix.

The 3-story home is built of painted brick with a wood shake roof and includes a long, shaded veranda where the family spent many afternoons. Typical of the Victorian style, it is adorned with “gingerbread” accents and dormer windows. The family had picnics and played croquet on a generous lawn that separated the house from Central Ave. This part of the property was later subdivided and a much newer residence now sits between Central Ave. and the Murphy house. In order to see the home, you must drive west on Orangewood Ave. and even then, it’s hard to see!

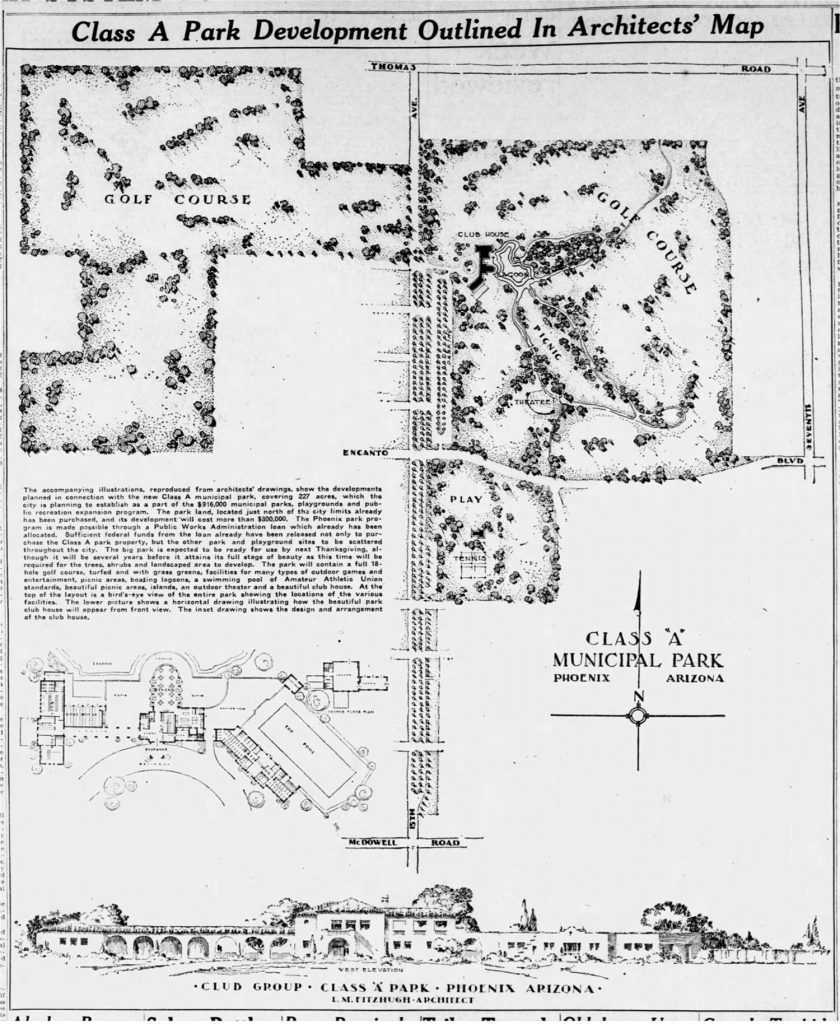

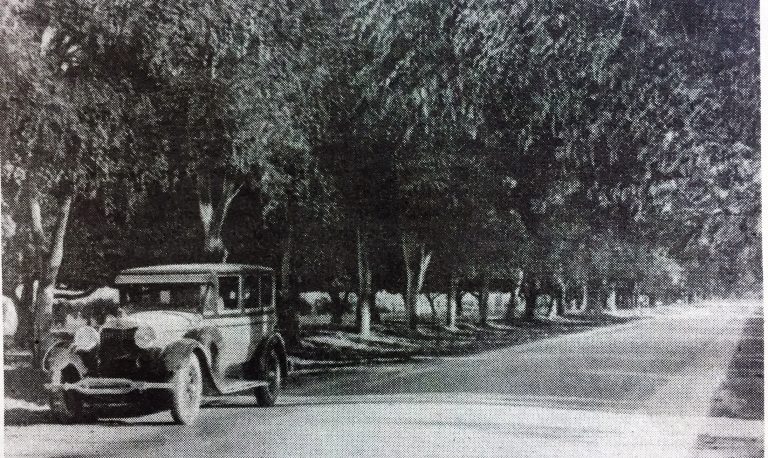

The distinctive streetscape along Central Ave. from Bethany Home Road to the Arizona Canal was Murphy’s creation and looks today very much as it did in the late 1800s. He was responsible for planting rows of Ash and Olive trees along the irrigation ditches that run paralleled to this part of Central Ave., and for establishing the Murphy Bridal Path*, a multi-use path that runs along the east side of Central Ave. The streetscape from Bethany to the Arizona Canal is on the Phoenix Historic Register, and has been nominated to the National Register of Historic Places.

*The path was named for Murphy in the 1940s by the Arizona Horse Lover’s Club

Historical photos courtesy of the Arizona Historical Society and the Arizona Capitol Times.