1720 W. Elm Street

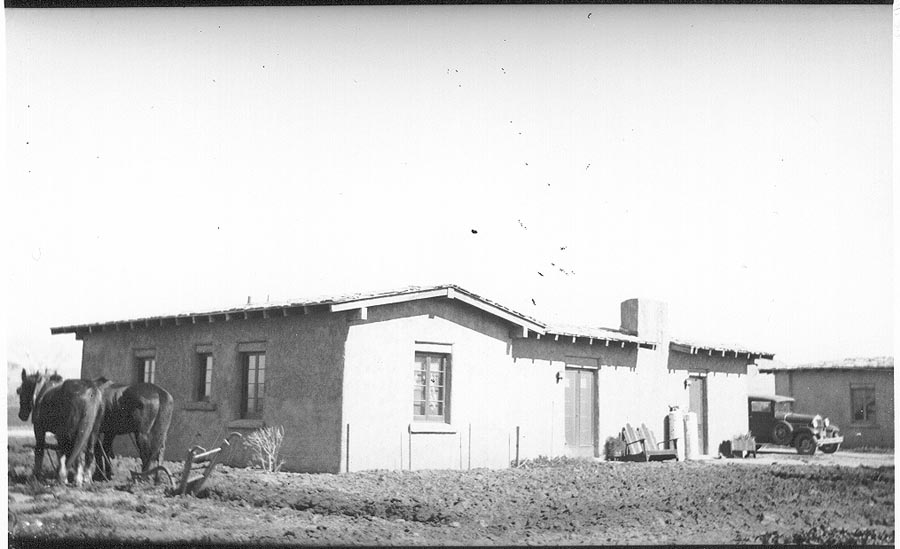

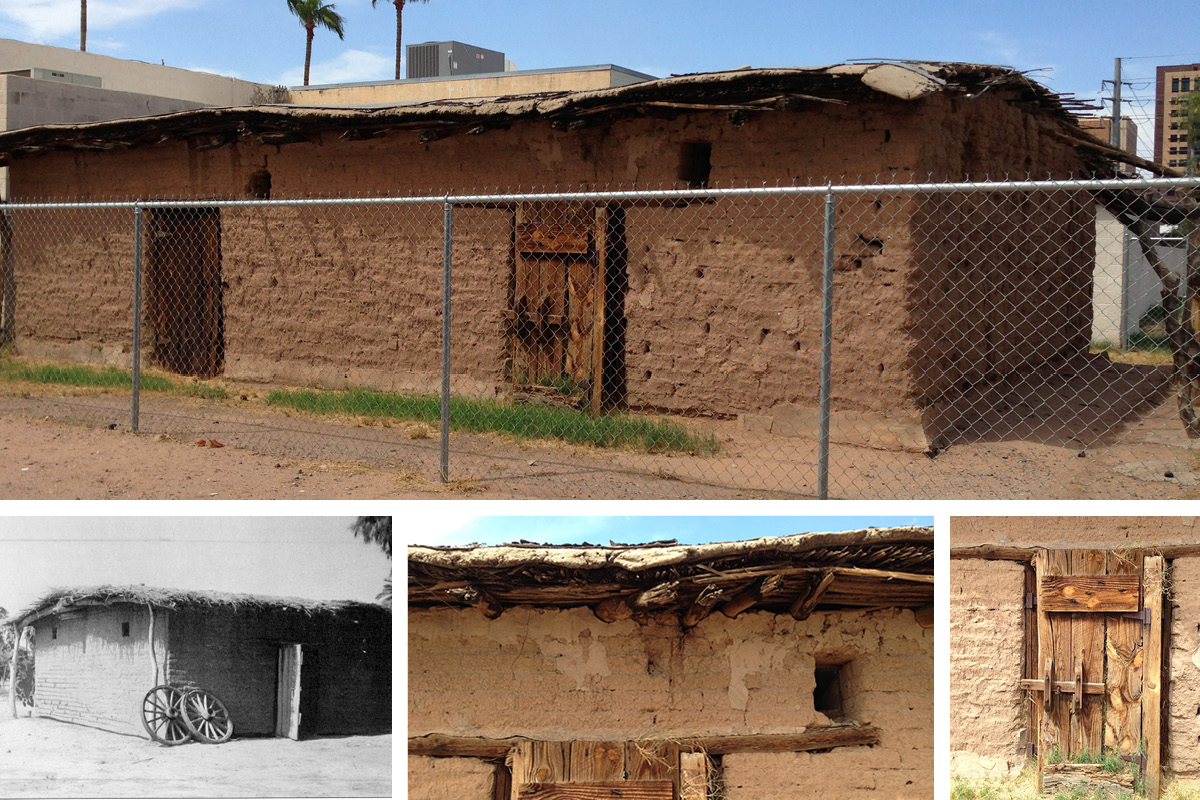

There aren’t many adobe homes in the Valley, and there are even fewer with exposed adobe exteriors. One article I read suggested there were only four, but I already know of four so my guess is there are likely a few more out there. Exposed adobe is unusual because adobe is made of unfired mud bricks, which will melt if too much water gets on them. Usually adobe homes are plastered with either a concrete stucco material or mud plaster, to add an extra layer of protection.

This particular home is pretty cool because it was designed and built for Daniel Boone and his wife Clara. Daniel was a descendant of THE Daniel Boone — American folk hero and frontiersman. The later D. Boone was the assistant general manager for the Salt River Power District. Though I tried, I couldn’t dig up much more on the Boones, especially Clara, so if you have some information, please enlighten me!

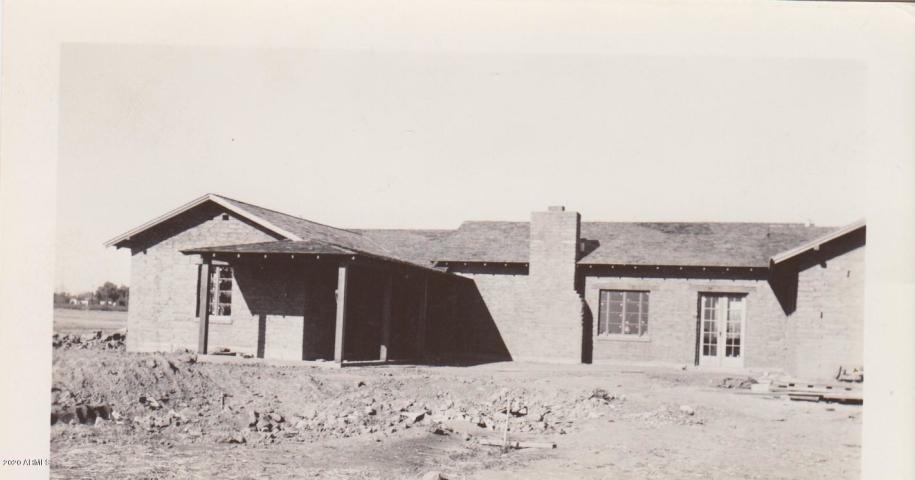

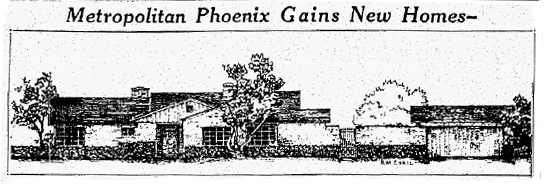

In 1940 the Boones built an adobe home on a very large parcel outside the Phoenix city limits. It was designed by architect Rolf M. Eskil and built by T.Y. Leonard. Eskil studied architecture at Berkeley and worked in L.A. before moving to Phoenix for a brief time. He was successful here and his designs were often featured in the Arizona Republic. At this time, adobe was not a primary building material in Phoenix, and when it was it was mostly used for Spanish Revival homes. So it is unusual that in 1940 the Boones would elect to use adobe and use it for a ranch-style house. If you are a reader of this blog, then you likely read about the Stewart Howard House, another exposed adobe ranch-style house built in 1937 just a few miles away.

The Boone house has steel casement windows, thick wood lintels over doors and windows, and a combination of exposed adobe, knotty pine paneling and plaster on the interior walls. The original floor was stained concrete but is now covered in wood laminate. The living room has an unusual fireplace that is referred to as a “pueblo hanging” design in an Arizona Republic article from 1940. The exterior is completely built of mud adobe with a low-pitched roof, originally covered in wood shingles. A rectangular bay window, clad in redwood siding, creates a focal point at the front of the house.

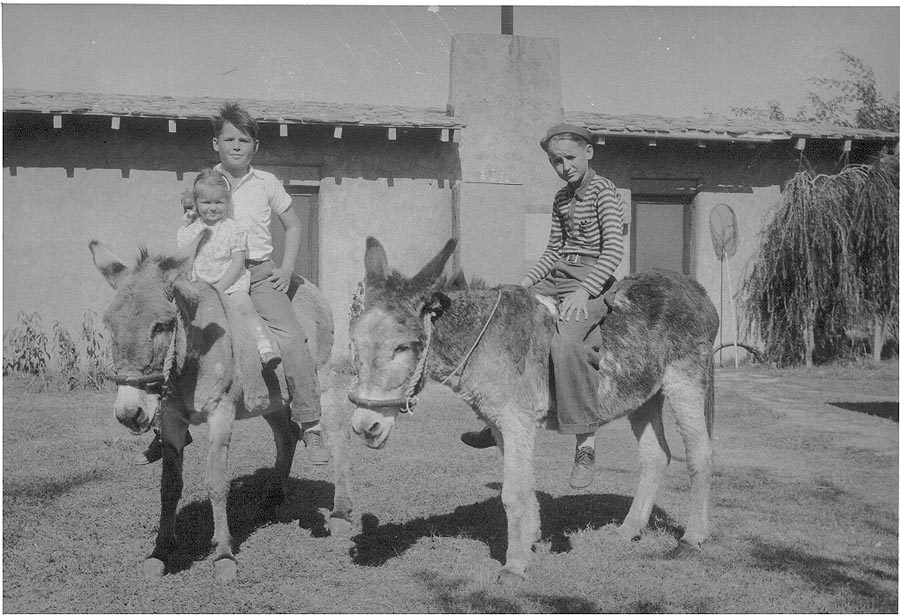

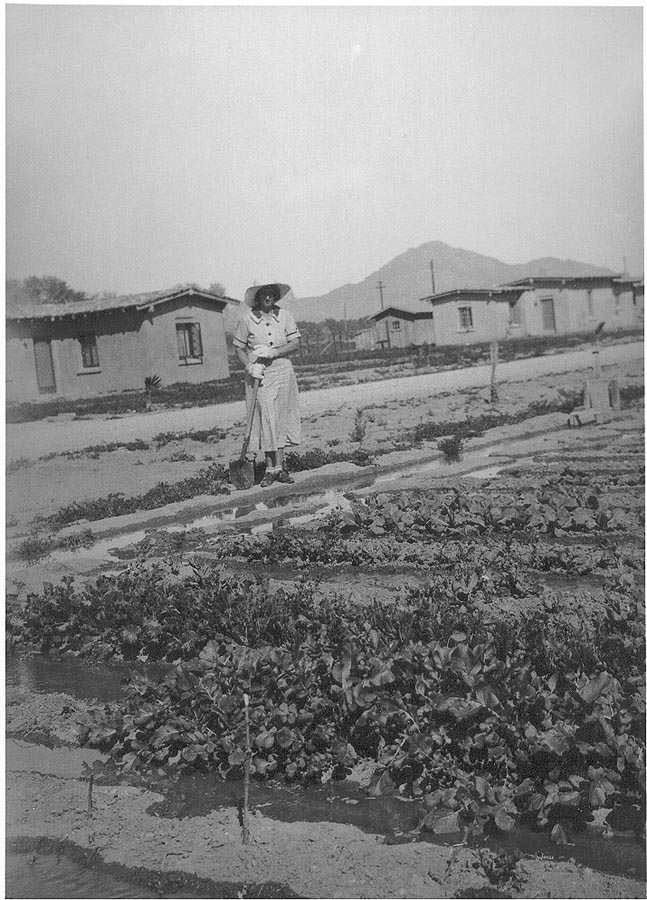

Daniel died in 1954, but Clara continued to live in the house until she died in 1987. The house has changed hands a few times since then, and minor changes have been made to the interior but the floorplan remains unaltered. The large lot, which the Boones used to raise cattle as a hobby, was subdivided during their lifetimes. Now the house, while still on a large lot, is surrounded by newer houses in the Elm Acres subdivision. The Daniel and Clara Boone House was added to the Phoenix Historic Register in 2005.

Historic rendering courtesy of the Arizona Republic